When I turned 18 I got my driver’s license. I was a late bloomer. Almost immediately after that I got my first video store membership. Family Video dominated in my corner of Indiana. I’d guess because almost no one had Internet access, and Family Video had “adult” titles, cordoned off behind swinging saloon doors in the back. I never explored it, even out of curiosity (I could manage with dial-up). For me Family Video was a reservoir of films I had heard and read about for years, but the local library would never stock. And because this was the era of transition to DVD, nearly everything on cassette was for sale. I watched Terry Gilliam’s Brazil on VHS. Then the next week I bought that copy.

My world opened up dramatically. I don’t know who originally stocked the Kendallville location, but his or her efforts fostered the crash course in film I undertook during the year worked for the local newspaper before college. I saw a lot of Woody Allen. Some Jim Jarmusch. Filled a few glaring gaps like The Godfather. And I saw David Lynch for the first time. I’d heard a lot about David Lynch. Mulholland Drive had just come out and critics adored it.

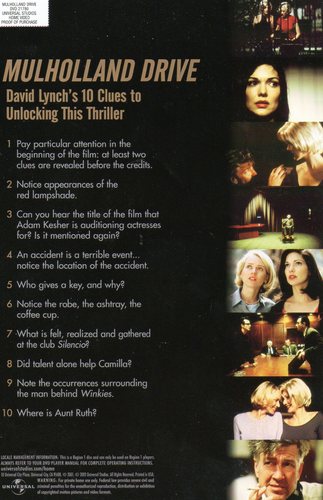

Lynch had a reputation. He made enigmatic, surreal films, and viewers spent hours trying to make sense of things that seemed senseless. In the case of Mulholland Drive, Lynch offered a possibly insincere helping hand. In the DVD release he included “David Lynch’s Ten Clues to Unlocking This Thriller,” hints at the truth behind Mulholland Drive‘s nightmarish story. Some writers on the Internet made an obsessive effort to follow the clues. Others thought the clues were actually red herrings that deliberately lead away from the truth. Either way, they felt certain a key existed, if they could just find it. The fact that Lynch foregrounds a blue key in the plot of Mulholland Drive seems like a wink and a dare. But the keys to a nightmare are within the dreamer. There aren’t answers, just interpretations.

I rented Lost Highway that year. I had read that Lynch made puzzle boxes and I felt determined to solve this one. I had the house to myself so I put it on the bigger TV in the living room. I sat down with a yellow legal pad in front of me. I scribbled notes while I watched. I didn’t see any secrets. I didn’t know what happened. But the movie terrified me.

When it finished I looked at my notes. None of them connected to one another. I felt stupid. I didn’t feel duped, just dumb. I had failed to solve a puzzle. I wasn’t satisfied. So I put the note pad aside, and I started the movie again from the beginning. The second time I didn’t analyze. I just experienced the movie. I still didn’t know what happened. I felt afraid. I couldn’t check closets or the basement for the monster, because the movie hadn’t given me anything specific to feel afraid of. It’d made me scared. I didn’t know why.

The next week I bought that copy, too. I watched it at least a dozen times.

During the seemingly infinite year before college, I received an unexpected invitation to visit a friend — a childhood crush — in a nearby city. I brought a recently discovered favorite movie: River’s Edge. I should have known that the story of teens covering up the murder of one of their friends probably shouldn’t have been my first choice. But I had started feeling artsy and wanted to impress her. I really wasn’t prepared for the visit.

First, she’d rented Mulholland Drive — feelings swelled. Second, she lived with her boyfriend — feelings crushed. But she was still my friend, so I made the most of the evening. We ate dinner. We watched River’s Edge. Her boyfriend came home. We watched part of Mulholland Drive. Her boyfriend went to bed. She went to bed. So I sat up on the couch, feeling very emotionally confused, and watched Mulholland Drive alone. At about the middle I threw up my dinner. I didn’t know what happened in the movie. But I knew exactly what it was about. In my gut. And then in that trash can. And finally sleeping alone on the couch. I left early.

I eventually saw an interview with Lynch. I realized I’d probably understood him best watching Mulholland Drive alone that night. Lynch was putting symbolism in his movies, but it was intuitive. It didn’t literally mean any one thing, it was symbolism for something vague, for a state of mind rather than a fact. It’s the work of a man who famously conceived of Twin Peaks’ Black Lodge inspired by putting his hands on the burning hot roof of a car in the LA sun. Someone who staged a shot in Wild at Heart with a man in the background carrying red pipe because that felt right. Focusing on these little oddities obscured the meaning of the movies.

I eventually saw an interview with Lynch. I realized I’d probably understood him best watching Mulholland Drive alone that night. Lynch was putting symbolism in his movies, but it was intuitive. It didn’t literally mean any one thing, it was symbolism for something vague, for a state of mind rather than a fact. It’s the work of a man who famously conceived of Twin Peaks’ Black Lodge inspired by putting his hands on the burning hot roof of a car in the LA sun. Someone who staged a shot in Wild at Heart with a man in the background carrying red pipe because that felt right. Focusing on these little oddities obscured the meaning of the movies.

Eventually I saw Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks in college, both of them with my wife. I still had my VHS copy of Lost Highway, and felt inspired to see it again. Watching it as a married man I understood that I had been right to feel afraid. It’s really a horror movie. But the monster – or one of the monsters – is the fear of infidelity. The creeping sensation that you can never be sure of your spouse, and you can never be sure of yourself. It dealt with fears I had no experience with when I first watched the movie. I didn’t have to worry that someone I’d let closest to me might be someone I couldn’t trust. Or worry what would happen to me if I thought that trust had been broken. I didn’t have any misgivings about my marriage, but you don’t have to believe in ghosts to be scared by a ghost story.

That’s how traditional horror works. It’s an abstraction that finds a back door to our fear. The grittiest, most realistic horror still works against the fact that it is improbable. Even basic murder is statistically unlikely. Let alone alien invasions, mutated monsters, or soulless mass murderers. The best horror is effective, even at its most farfetched, because it contains an element of something much more common that we fear. Often it is just each other. John Carpenter’s The Thing, Night of the Living Dead, Texas Chainsaw Massacre. All contain the basic fear that we can’t trust other people. Lynch’s horror is often about that, but just as often its about the fear that we can’t trust ourselves.

Eraserhead I saw last. It is the most like a horror movie of all. It’s also the most surreal, but its topic is the most universal: The horrors of adult life. Fear of intimacy, fear of family, fear of sex, fear of fatherhood. Ultimately, the fear of responsibility and the fear of failure. The movie is unsettling because of its grotesque imagery. But it’s even more unsettling because the horrors it represents aren’t unusual. No ghosts, no masked killers. Just the anxious experience of living life. And the fear that life might be too much for us.